A Sober Australian Overview of the AI Value Chain

Who's going to make all the money in AI? And how do policymakers make sure it's me.

Who’s going to make all the money in AI? Where does the value accrue?

What should Australian policy makers do to ensure Australia gets a slice?

This post was inspired by a conversation with a policy guy, and a post in the Down Round Discord by user Jdoggg.

Here is a simplified version:

I have put an extended version of the above chart at the end of the article.

Additionally, I have included my take on potential national policies that should be considered for the various segments of the value chain. I’ve broken the policy proposals out in each section: feel free to skip them if that’s not your bag and you’re just here for the business of AI.

Here’s a summary for people really short on time:

1. Applications

The top layer of the value chain. Or bottom, depending on your perspective.

The layer you use every day. Think ChatGPT.

This layer includes any service or app that uses AI extensively.

There are three sub-categories within Applications:

Integrated apps by companies that have their own models.

Wrappers building on top of models they don’t own.

Legacy Software As A Service - Established enterprise software that will have significant AI integration.

1a. Integrated Applications

Examples: ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Doubao

Value capture: moderate

ChatGPT is built by OpenAI using their own LLM, image and video models. Google’s various AI services are built on Gemini. Integrated players are able to deploy their latest models into their own products, and receive user feedback to further advance the models in a nice flywheel.

Additionally they have a pricing advantage over wrapper applications who are required to pay a margin to the underlying model makers.

There is a slim chance this is a winner-take-all market, which would make the value capture obviously very high, but I do not subscribe to this belief.

There are large input costs to running the underlying model, which will be discussed later.

Policy Considerations

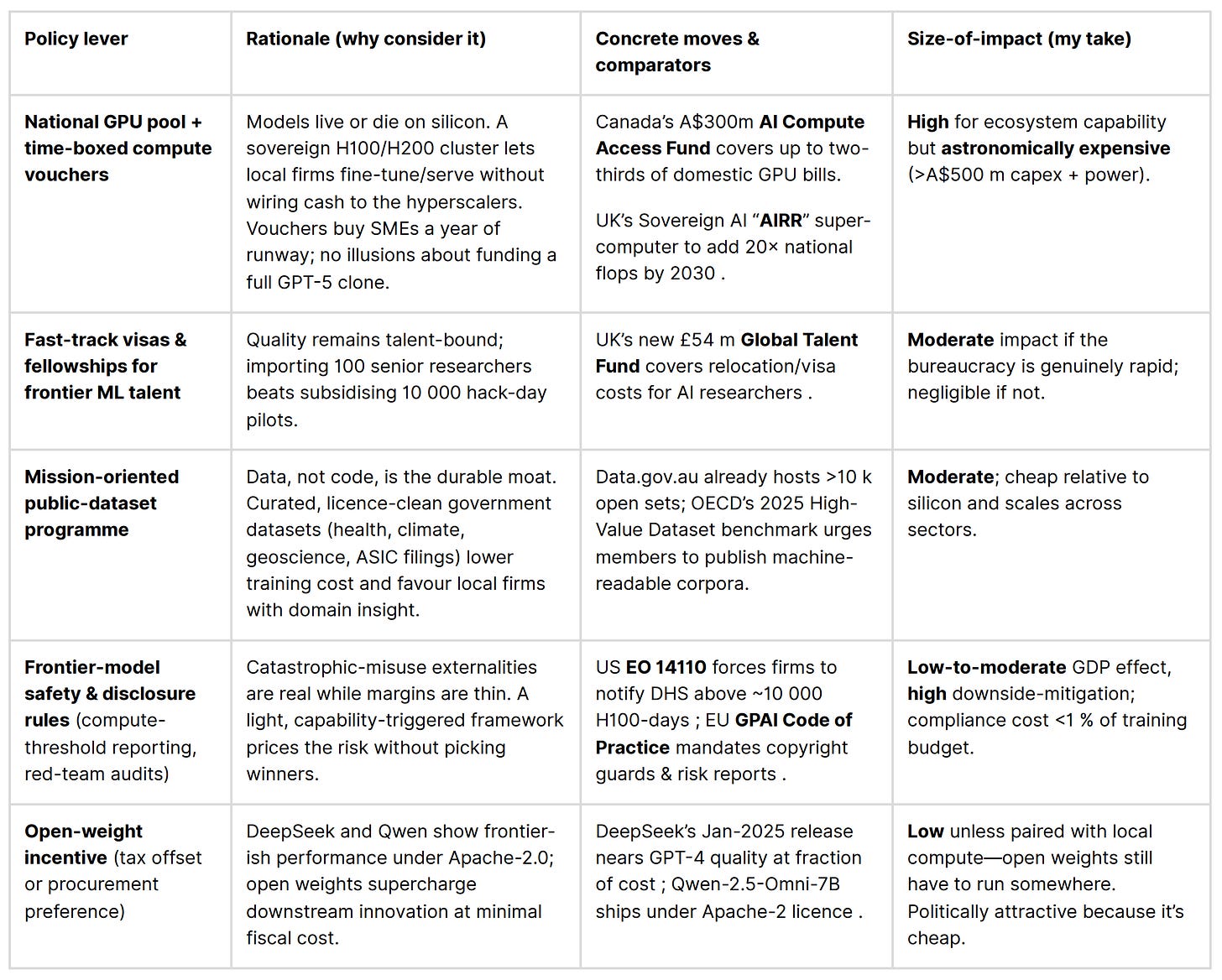

(Sorry that it’s an image, SubStack doesn’t allow tables natively)

Should policymakers bother with integrated-app levers at all?

I would suggest policymakers;

Spend the scarce regulatory energy on data portability and interoperability rules now, before first-mover apps cement in their own ecosystems - ideally taking a multi-lateral approach.

Skip cash hand-outs or tax breaks – they won’t shift the frontier in a space already drowning in VC money and a horse that has already bolted.

Monitor the situation: if integrated apps ossify into unavoidable distribution rails à la iPhone OS/Android, escalate to stronger conduct obligations, again, ideally working multilaterally.

1b. Wrapper Applications

Examples: Perplexity, Synthesia, Cursor, the multitude of low-rent App Store apps for AI Face Tuning, Plant Identification etc.

Value capture: low

Pieces of software that rely on other company’s models. Many of the new entrants here will be eaten by the Integrated Applications.

An app like Perplexity, the AI search engine, was novel for about 9 months until ChatGPT added internet search, Google Search added more AI, and all Integrated Applications followed. Most consumers can not justify a Perplexity subscription in addition to a ChatGPT subscription that includes the same features.

The company Synthesia makes AI avatars for marketing videos or product demos. It is cool tech, but this is a feature that is likely to become part of Meta or YouTube’s ad platform where Meta can create an infinite number of unique marketing videos uniquely targeted to the viewer with limited input from the ad buyer due to owning the customer data.

The same is true for many of the video editing, music making, image generation and AI coding wrappers. E.g. Windsurf.

Small amounts of value can be captured by companies that are niche enough to not warrant becoming a feature in an integrated application, but complex enough that it can’t be easily spun up by customers with increasingly sophisticated AI coding tools.

Examples: Environmental tracking for mining operations, pharmaceuticals, surveying software or other localised solutions with smaller TAMs and various stakeholders.

Or apps that the bigger players won’t touch for reputational or regulatory reasons e.g. explicit companionship apps, sex-bots, gambling wrappers, AI pornography etc.

Policy Considerations

My advice for policymakers regarding AI wrapper applications

Do not spray broad grants across every gimmicky wrapper; survival odds are grim once integrated apps absorb the features with any value.

Do offer narrowly-scoped compute credits and sandbox space for the rare wrappers attacking thorny, regulation-heavy niches.

Lock in a fair-dealing code for model-API providers before margin-squeezing becomes the norm. It’s cheaper than perpetual hand-outs.

1c. Legacy SAAS Applications

Examples: Jira, ServiceNow, HubSpot

Value capture: short term moderate, long term high risk of business model collapse, except highly regulated/integrated circumstances.

Legacy enterprise SAAS companies with a sufficiently large enough user-base, sophisticated sales and distribution systems and lock-in will likely benefit from AI in the short term, but in the long term could see their product become increasingly abstracted away by AI interfaces and eventually replaced by integrated players.

Companies such as HubSpot, Atlassian & Xero spring to mind here. Deeply embed software with large databases, and potentially regulatory integration.

AI will increasingly become the human interaction layer on these apps, as is already the case. I can make tasks in Jira with natural language, and get automated messages in Teams updating me on their status. I am then using the same Teams chat to say “change that task to done, get Bridget to come up with a UI for this new feature” or even “show me a birds-eye view of where this project is at” and receive an on the fly interactive data visualisation and summary that I can query with natural language.

Then what is the need for specialised project management software? Microsoft, the ultimate AI wrapper inevitably wins the enterprise, maybe with Google picking off some of the newer entrants with Salesforce being the wildcard.

Obviously the legacy data and the complexity of custom integration is useful here and creates significant lock in that won’t be disrupted in enterprises for some time. Hence some short term revenue increase: pay the extra $30 per seat for AI features. But new businesses will adopt newer methods, and with time enterprises will determine the pain of the database migration (which may be lessened if AI coding gets better) is worth it for the benefits of integrating with a full service player.

The examples above are possible with the AI technology we have right now. I am not factoring in the speculated future of ambient AI or layers of agents interacting with each other where human decision making is deprioritised.

Enterprise or large scale software that is less easily disrupted are businesses that include a real world features, such as Point of Sale, or are plugged in to complex, regulated spaces, like payment processing, healthcare or telecommunications.

Policy Considerations

My take

Data and API openness are the only levers that matter. Without them, Copilot (or Gemini + Workspace) will steadily cannibalise Jira-like UIs until the migration pain is the last moat. AI coding is shrinking that pain.

Subsidising AI retrofits keeps local engineers employed for a few cycles but won’t stop UX abstraction. It’s a jobs program, not a competitiveness fix.

Conduct rules must land before the integrated suites hit unassailable scale. After that point, enforcement becomes a decades-long legal whack-a-mole. This is the take I have least confidence in, as platform integration does often benefit consumers in the short term, as well as privacy and security, e.g. Apple Wallet. Policymakers must tread carefully.

Final Take on AI Applications

The big platforms will likely eat almost everything. The value lies in anything ugly, local, legacy, highly regulated or niche. But not enough to build a national AI strategy around.

2. Distribution

Examples: Apple, Google, Meta

Value capture: High

Distribution is a gate-keeper layer in the value chain.

This is the platforms that AI applications exist upon. This includes:

Operating systems such as Apple devices and AppStore, Google Android,

Advertising networks like Facebook and Google, and

Productivity suites like Office 365.

Every month Apple gets between A$4.50 - $9 of your ChatGPT subscription if you signed up on iPhone.

In order for a business to grow, it typically requires Google and/or Meta to serve ads.

This locks in the dominant players. Google, Meta and Microsoft have a built in advantage with their distribution - they can add features to their products that hundreds of millions, or billions of people already use.

Which makes the rise of ChatGPT so impressive. But despite their organic virality and growth, they still pay Apple and Google a percentage of revenue. Additionally, their ability to fully integrate into their customer’s lives is hampered by the restrictions set by the platforms. Hence both OpenAI and Meta’s ambition to build an independent device and fully own distribution.

Policy Considerations

My Take

Distribution, not models, is where the unproductive super-normal rents sit. Address the rentiers and the entire downstream ecology gets oxygen.

Payment choice is the quickest, cleanest cash transfer from gate-keepers to creators. Everything else is second-order.

Ad-tech separation is a shiny prize but also a bloody fight. Greater competition and transparency should exist, but price benefits to customers are unclear and a decade long fight is assured. Follow US/EUs lead.

Conduct rules must land before default AI assistants ossify into the next App Store on iPhone moment. After that, it’s whack-a-mole forever.

Another alternative: a good old fashioned shake down1.

3. Model Makers

Examples: OpenAI, Anthropic, Google

Value capture: Medium/Low

The AI models that power the application layer. The most famous of which include OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, Meta’s AI, Elons xAI, Deepseek, Qwen amongst many many more, including in other modalities such as text-to-speech, image generation, video generation, music generation etc.

Currently these models do not have pricing power due to the high level of competition, and the negligible switching costs for customers.

At any one time the “best” model will belong to either Anthropic, OpenAI or Google. Time will tell as to whether one player will emerge above the rest, develop “Super Intelligence” and it will become a winner takes all market. My prediction is it won’t be, and we will continue to see competition for some time.

There are some benefits here for legacy businesses with proprietary datasets that can be leveraged to train AI models. Meta has everything on Facebook and Instagram, Google has your emails, search history, photos, YouTube, traffic data, maps date, Google Music, Android etc.

There is further margin pressure from the “open weights” models, largely dominated by Chinese players, who make it very easy to “fork” and create alternative, or customised models including potentially optimised for cost. Notable mentions being Qwen, Deepseek, Mistral & Llama.

As such, AI models as a service will likely be low margin, with significant regular upfront costs for new model training.

The real potential for margin is leveraging one’s own model technology into integrated apps, such as ChatGPT, Claude, the Google Suite, the Microsoft Suite etc.

There may be value in building models with specific proprietary data for specific, niche industries, however it is likely most efficient to fork existing open source models or use simple tools such as Google’s AutoML, rather than ground up builds.

Entering the model development industry requires access to two things: talent and computational resources. And I’m afraid the ship has left the station on both of those counts.

Talent now apparently costs US$100mil to import, or takes several decades of education policy to develop. And the compute costs are astronomical, but we will get to that later.

Policy Considerations

My advice to policymakers

Don’t chase frontier training for its own sake. The capex curve is ludicrous, margins are razor-thin, and any competitive edge vanishes in six months.

Do bankroll a shared GPU pool. But understand it’s national research infrastructure, not a profit centre.

Talent visas beat domestic STEM pipelines for the next five years. If Canberra can’t clear a four-week visa cycle and implement flat fees, forget it.

Publishing first-rate government datasets is a bargaining chip. Tens of millions, not billions, and it feeds every layer above.

Safety rules cost peanuts and buy political cover. Somewhat of a distraction, but get them in early to avoid a face-saving scramble after the first public model meltdown.

Open-weight carrots are nice PR but won’t move the needle without compute and data to match.

The last point is really only in there with a pin in it as I want to write about a larger national open source policy in a future article.

4. Data

Examples: Book repositories, ScaleAI

Value capture: Low

Models require structured data to be trained on. The better quality the data, the better the output. Two subcategories here:

Raw data. All the major models have ingested most of the internet. They now turn to data companies such as ScaleAI (recently valued at ~USD$29b) to create, refine, tag and structure data that then trains the models.

There is opportunity here for niche players with niche datasets to create specialised markets. E.g. A company that licenses access to every surveying company's proprietary data, and licenses it to a business that builds surveying software. Publishing high quality public datasets are a priority for policymakers here.

Data Structuring. Databases, data warehouses and data lakes. Specific companies that ingest, organise, validate and make the data accessible are essential. E.g. Data Bricks. Australia has none of these and entering the market is difficult.

Policy Considerations

Open, high-value public datasets are the single cheapest lever. This should be a priority. $50m spreadsheets vs $500m GPU farms. Allows local start ups to compete against AI giants for localised market.

Annotation subsidies only make sense if paired with local compute, national interest and clear export demand; otherwise seems pretty pointless. I was trying to come up with something to address the issue.

Data trusts are a governance fix, not a cash cow. Still worth it for mining/health verticals where privacy law blocks collaboration.

Sandboxes buy political cover and de-risk SME experimentation. Do them, but keep them lightweight.

Data-portability rules are the long-term competition play. To reiterate: without them, the distribution gatekeepers will simply recreate lock-in at the data layer.

5. Data Centres

Examples: Amazon, Microsoft, AirTrunk

Value capture: Moderate/low

Data Centres perform three main tasks when it comes to AI;

Host AI applications.

Provide compute to train models.

Run inference. That is, whenever you ask an AI something, it uses computers in data centres to run the equations to work out the answers.

The biggest public data centre operators are the hyperscale cloud infrastructure hosts, such as Microsoft, Amazon, Alibaba and Google. Businesses build and deploy software on their managed platforms. They are very sticky services with high switching costs.

The other tier of data centre operators are the more specialist modular compute providers. You can either store your computers with them, rent their computers from them, or offload adhoc high-performance workflows to their infrastructure.

Locally this includes data centres like AirTrunk and NEXTDC. Often the lines are blurred between the hyperscalers and this modular tier, as cloud providers often partner with the modular data centre players. For example, the app you are building on Amazon’s AWS is deployed on a local AirTrunk server stack. AirTrunk charge Amazon, Amazon charges you.

Additionally, private companies have their own AI data centres. For example, Meta likely has the most Nvidia GPUs in the world.

In our value chain, the AI model makers like Open AI pay data centres to do the computations when you ask their model a question, or to train their models.2

Alongside salaries, model makers’ major cost centres are model training and inference - both of which involve data centres. With training costing something like A$100m for GPT4.0, and OpenAI spending an estimated A$6b on inference compute costs last year, the model makers are beholden to data centre operators for their core business, which is why you see them partnering up: OpenAI with Microsoft, Anthropic with Amazon. It is also another aspect of their margin squeeze.

Can Australia extract value from data centres?

There are benefits to data centres being close to the users accessing them, both for performance reasons, and for regulatory compliance regarding data governance.

As such, there will always be a local market for local data centres, however there is also a fair amount of competition. Additionally, as a modular data centre operator, your biggest customers are often also competitors who have high negotiating leverage.

Data centres can attract foreign capital through renting to large multinationals, but the use is somewhat capped by our own domestic consumption, so while a fine business, the current paradigm is not something from which Australia can gain outsized benefit

The one area of competitive advantage Australia does have is the future potential of access to abundant renewable energy as well as solar expertise. This may bear cost advantages as electricity consumption is a major ongoing expense for data centres. It also aides with excess grid capacity issues arising from fluctuations in renewable generation.

Were corporations to make environmental commitments or have environmental commitments imposed on them, this could see the model makers and cloud providers offloading compute functions to Australia’s greener data centres, particularly in less time-sensitive applications, such as model training.

There is some opportunity in niche products for data centres, such as cooling technologies, (e.g. companies like DUG show some limited promise with a bunch of caveats) however Australia’s domestic capacity for high tech manufacturing is limited.

Policy Considerations

My take

Green-power zones + planning certainty are the only levers with real bite.

Australia can win time-flexible training workloads if renewable tariffs are attractive; live inference will stay near end-users overseas.

Cooling R&D is niche. Worth supporting, but don’t pretend it will birth Nvidia II.

Data-sovereignty rules need to be surgical. Over-reach and the giants will simply route traffic through Singapore.

6. Chip Designers

Examples: Nvidia, Broadcom, Google

Value capture: High

Chip designers sell their chips to the data centres.

Right now I think it is fairly empirical to say that this is where the bulk of AI value has accreted.

Or at least, $3.5trillion USD of value.

Nvidia market cap September 2022 (just before ChatGPT’s release): $305 billion USD

Nvidia market cap today: $3.89 trillion USD

They have a near monopoly on the high powered chips that power AI workloads and as such can charge a staggering 75% margin on their products. Demand for their chips outstrips supply.

Their biggest short term risk is government export controls compressing sales to China in particular (however could see it expanding). Which in turn becomes a medium to longer term risk as China accelerates the development of their domestic leading edge chip manufacturing. For example, Huawei’s chips currently power DeepSeek inference.

The other significant player in the space is Google, with their proprietary TPUs, which they have used to power the machine learning recommendation engines behind their search and ad serving algorithms. Which highlights an issue with Nvidia’s margins - if your customers know they’re getting squeezed, they may end up your competitors. All the hyperscalers are building their own chips.

However chip designing is complex, to say the least. This means there are many aspects where value can be created and extracted. For example, companies like Synopsys and Cadance who make software for designing chips have a combined market cap of ~USD$175b.

All that money suggests that there should be opportunities for international players like Australia to participate in the design aspect of chips. Unfortunately there is only one listed fully-commercialised Australian IP block that directly accelerates neural network technology today: BrainChip, and they are a relatively small player.

Australian universities create around 300 micro-electronics engineers a year. Compare that with Taiwan’s annual demand for ~10 000.

Hard to be a player here without decades long investment in a particular niche of chip design.

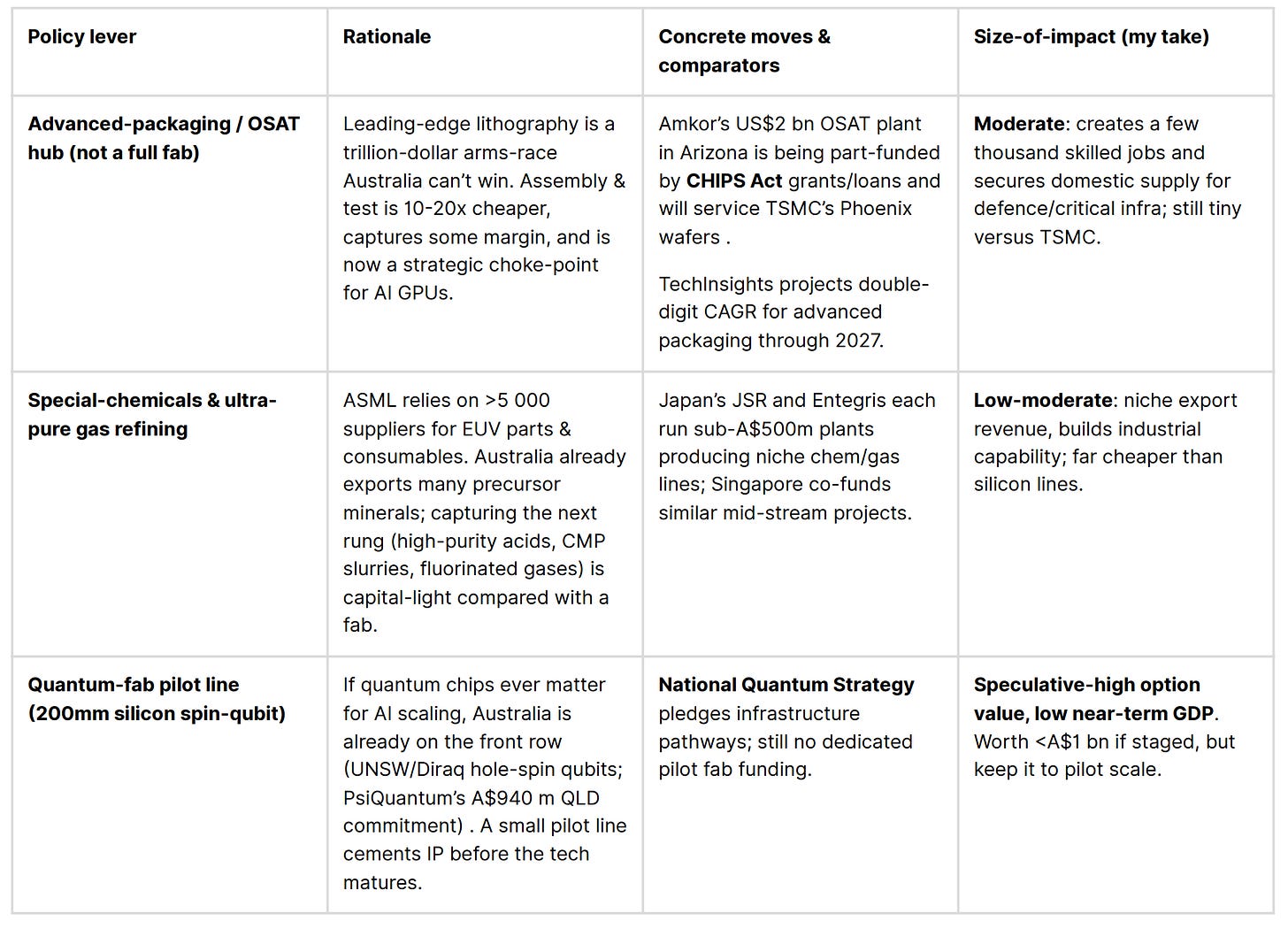

Policy Considerations

My Take

No quick wins: chip design is a 15-year game; any lever short of sustained talent, tooling and capital is cosmetic.

Quantum R&D is a moon-shot with genuine upside; fund it sensibly alongside the National Quantum Strategy, but keep expectations realistic.

Tax credits & co-investment help, yet won’t dent Nvidia’s dominance without decades-long patience.

Export-control arbitrage could yield boutique revenue but don’t build a national strategy on geopolitical whiplash.

Basically: unless Canberra is ready for decades-long, multi-billion dollar patient capital, the realistic play is small, sharp interventions such as shared EDA licences, talent drives and laser-focused niche IP bets while leveraging Australia’s broader renewable-powered data-centre story to stay relevant in the AI silicon race. That and crossing our fingers that quantum works out.

7. Fabs

Examples: TSMC, SMIC, Samsung, Intel

Value capture: High

The factories that take the chip design, and make the chips. TSMC is the biggest player here, and their leading edge transistor technology enables Nvidia designers to keep pushing forward the capability of their chips.

TSMC have always had relatively small margins considering their importance in the value chain, however that is changing. Historically the small margins have been because companies like Apple and Nvidia ensured they have a somewhat diversified supply chain, and part of the commitment is the expertise and upfront investments these companies make to the fabs in order to enable newer chip development. Profit came years down the line once fabs were fully depreciated and the chips are no longer leading edge, but still useful.

But as TSMC has pulled ahead of competitors and production cycles have shortened, they have been able to more recently grow margins.

There is no world where Australia or other middle powers can hope to compete with Taiwan, South Korea or China in chip fabrication, let alone the leading edge where the value is accruing. Even the great United States with their partnership with TSMC will always be at best producing chips that are 2-3 years behind the leading edge.

Suppliers to the chip fab giants can be giant industries in their own rights. Famously, ASML, the Dutch manufacturer of the lithography machines that are used in fabs has a market cap of €264b. They themselves have over 5000 suppliers.

However there is no record of any being Australian.

That is to say, Australia has no high tech manufacturing capability in this space.

Adjacent industries such as advanced packaging have lower barriers to entry and are increasingly important to the manufacturing of advanced AI chips. Australia has a potential renewable energy advantage here, but even our geographic advantages are bested by the likes of Malaysia and Vietnam. With some heavily targeted funding there is some potential to develop an industry, creating several thousand high skilled jobs, although it will take an intervention that would make most governments uncomfortable.

Niche chemicals and gas can generate significant revenue, and Australia does have the raw deposits of many of the chemicals. There is some potential to move up the value chain here, but processing niche chemicals comes with its own specialisation. Most chemical companies are decades old. Not to mention the environmental and regulatory hurdles.

Quantum chip pilot lines are another moon-shot that can be pursued with the understanding that most suppliers will likely be international due to the lack of high tech industry in Australia.

Policy Considerations

My Take

Forget about wafers. Even the US will trail Taiwan by a node or two.

Advanced packaging is the only fabrication-adjacent niche with realistic ROI; it leverages our renewable-energy story and doesn’t need a US$20bn cheque.

Mid-stream chemicals/gas refining is a modest but bankable play given Australia’s mineral base. Still feels like it would take a level of investment and industrial policy that would make many people uncomfortable given the lack of established knowledge.

Quantum pilot lines are a lottery ticket. Worth a punt, know your limits.

8. Raw commodities

Value capture: Low

The things needed to make the parts that make the chips and data centres.

These could be placed in three buckets:

Rare Earth Elements (REEs).

Bulk commodities: silicon, quartz, lithium, copper etc.

Speculative/”emerging” materials.

REEs

Rare earth elements' major issues are;

They are not actually particularly rare.

Chips use very little of them.

No one wants to refine them.

A lot of the classic REEs are as abundant as copper or tin, but are jumbled in with a whole bunch of ore. The extraction process is the hard and messy part. And by messy I mean the processing of the ore produces radioactive waste, which obviously comes with regulatory, environmental and social costs that are too much for most countries to stomach. That’s in addition to the large upfront investments and expertise needed to spin up the industry.

Many of the above are not issues in China, who consequently refines 90% of the world's rare earths. Despite this market dynamic, prices for REEs are volatile, the Chinese industries are heavily government subsidised, and supply is artificially constrained by quotas. As such, any windfall profits are suppressed. China’s subsidisation is more for longer term industrial goals and geo-strategic importance than economic development. Most of the significant profits come down stream in the finished components made up from the rare earths, such as magnets - a manufacturing industry that China also dominates.

Australia has one of the few non-Chinese processing plants, however due to our cost and regulatory disadvantages, as well as lack of downstream manufacturing sector it is still a challenging space to generate significant economic advancements, with two exceptions:

Environmental Advantage. Were there to be a significant global unified environmental regulations, and were Australia to pursue a path of “greener” refinement technology, with our abundance of renewable energy we could be the major player in green rare earths.

Corporations, including the likes of Apple, have environmental commitments that could lead to Australian refined rare earths justifying their inevitably higher price tags.

The counter here is that, with a few notable exceptions, there does not seem to be any serious global push in this direction as it is not in any of the major players short term interest. If anything much of the sustainability discourse has dried up.

The China Alternative. Great power geo-political machinations have led to the introduction of terms such as “selective de-coupling”, “China +1”, “friend-shoring”.

Out: Free trade, globalisation, liberal world order.

In: Economic decoupling, indigenous capacity, the Thucydides trap

There is a potential for Australia to attract significant Foreign Direct Investment from economies who see it as geo-strategically important to have an alternative to sourcing critical elements from China - particularly as China has overtly indicated that they see their dominance in REEs as a strategic strength - hence the heavy subsidisation and intervention.

Australia could be the only alternative to China, making a quasi-monopoly from which we can extract value.

Of course were the market to function effectively, the opportunity disappears.

I am uncomfortable with the idea that our incentives are misaligned with our largest trading partner - Australia would be in a position where it would be in our national interest to be globally lobbying for the boycott of Chinese REEs . An inadvisable position to build a national strategy around.

However, suppose it eventuates that manufacturers of the world require non-Chinese rare earths and are happy to pay a premium for Australian product. Taking advantage of that paradigm to channel foreign investment in the short term would no doubt create expertise throughout the process. This ideally leads to innovations in the technology, design and IP space that can be lasting, even if the world snaps back to buying cheaper Chinese alternatives.

Unlocking the space could lead to niche high-tech products, such as chemical compounds being developed further creating value.

Plus it kind of makes sense: we dig things out of the ground. It’s what we are good at down here.

Bulk Commodities

Commodities used for chips include high grade silica and quartz. These are relatively abundant globally, with any advantage coming from their refinement, purity and efficiency of processes.

Lithium is useful for battery production, which has uses in data-centres and AI devices however the exact same issues arise as with REEs - that is, China has indigenous reserves, refinement and world leading down stream manufacturing.

Australia has some advantages here, both in our natural abundance, a strong resources sector, and our relative geographic closeness to the chip making fabs across Asia.

Speculative and Emerging Materials

What will the chips of the future be made of?

Obviously one can speculate endlessly here, but a significant portion of these materials are either in the camp of being able to conduct at almost the atomic scale, or provide shielding at the almost atomic scale. Then there are all the quantum computing materials which overlap with the above.

Australia has good representation here, with a good research layer, access to the raw materials, institutional knowledge and public/private commercialisation pipelines such as through the CSIRO.

Australia is a world leader in quantum materials, however, as discussed, there are legitimate reasons to be skeptical of commercialisation potential here. As with the above, worth having a punt on and could lead to other innovations were quantum to be bust.

Policy Considerations

Green-premium REE processing is the only sizeable bet that isn’t geopolitical roulette. It plays to renewables, reputation and existing Lynas capacity.

Government-backed offtakes crowd in private capital faster than blanket grants. Copy the US DoD model, but watch the price floors.

Ultra-pure bulk commodities are low-glamour but bankable; they monetise AU mining expertise without chasing fabs.

Recycling and speculative materials are long shots; cheap enough to try, but don’t bank on them for GDP headlines.

Beware the China-alternative fantasy: any AU push that relies on a lasting boycott of Chinese REEs puts national interest at odds with our biggest customer. It’s a good hedge, but a bad centrepiece.

In summary

AI value is currently largely captured by Chip designers in Nvidia, chip makers, and the integrated players.

That leaves Australia and other middle-powers in a tough spot, as the expertise, and cap-ex required to develop national capacity and competitors is more-or-less insurmountable.

For Australia in particular, moving upstream in the critical minerals pipeline is the most obvious bet. There is limited risk of the demand drying up or being disrupted, and there is already significant institutional expertise.

That, ensuring onshore AI capabilities, data portability, and having a punt at advanced speculative materials and quantum computing form the cornerstone of a Raph approved AI strategy.

Not a real suggestion

OpenAI have their own data centres that they supplement with third-party compute, primarily through Microsoft Azure.

Enjoyed this and appreciated the "sober" approach. I feel like I've been talking more and more about how the AI boom is locking in existing players rather than opening things up.

You mentioned visas in the "model makers" section but, if you broaden out the policy lens, you can also add in another opportunity for Australia: "Attracting and Retaining Talent."

Talent concentration might be the only part of the AI value chain that isn't already locked in. AI founders, devs, and researchers currently pick between Chinese political meddling, EU over-regulation, and the increasingly chaotic situation in the US.

It's a longer term play but through a combination of smart visa strategy, lifestyle arbitrage, and regulatory sanity, Australia could expand on our existing education export industry and become the country of choice.

If these policies were able to attract 200 - 500 of the right people, they could have as much impact as the more direct ideas in the piece. VC money would be attracted by a concentration of talent and we're off to the races. Remember that Anthropic started with 10 people, and Mistral with 3.

Fantastic read. First time I have seen a fellow Australian prioritise open data. Until we take this first small step, any policy makers talking AI shouldn't be taken seriously.

The one lever that trumps every shiny subsidy or moon-shot initiative you list is radical openness of high-value public datasets. Clean, well-documented feeds from transport, land, health and energy agencies would likely cost governments 10s of millions - not billions. But would unleash a wave of downstream model-training, SME product development and academic validation that no tax rebate or co-investment can match. Withholding state-collected information is fiscal irresponsibility at best, negligence at worst.

Until that tap is turned on, everything else is garnish. Open data forces the hyperscalers to compete on service rather than rent-seeking, gives domestic firms a home-ground advantage rooted in unique context, and would like deliver measurable productivity gains back to the Budget without the need for a new levy or bond program. If we truely want a home grown edge, we must publish the datasets and the rest will follow or be exposed as policy cosplay.